June 6, 2003

35 years, and the call echoes

Robert Francis Kennedy died 35 years ago today. I'm not sure America has gotten over it. I'm not sure we should.

Kennedy was beyond complicated. Much of his career was uninspiring, or worse. His stint with Sen. Joseph McCarthy hardly reflected high democratic calling. His subsequent public interrogations of Teamster officials could be ineffective and even childish. As a presidential campaign manager, he struck many as ruthless and Machiavellian. As his brother's attorney general, he was slow to warm to the claims of an historic civil rights movement -- though, eventually, as William Manchester has written, he became the only lead lawyer "to preside over a Department of Justice devoted to the pursuit of justice."

But the RFK that marked us, the politician that seared, was the Kennedy of his last two years, 1967 and 1968. His brother senselessly and brutally murdered, his father silenced by stroke, he experienced a new plane of agony, suffering and injustice. He came to feel viscerally Aeschylus' description of "wisdom through the awful grace of God." The voice he found, finally, was clearly his own. Wounds had opened his eyes wide to the plight of the powerless and marginalized. While his early speeches were pragmatic and ponderous, those delivered at the end of his life were deeply moving, lyrical, and even prophetic. He became a leader of the soul. And he bared his own for the rest of us to see. Perhaps he was no longer able to do otherwise.

Kennedy's late Senate career and his presidential campaign took the focus of our politics into the neglected byways of the nation. Embracing black kids with distended stomachs in Mississippi, highlighting shocking suicide rates on Indian reservations, marching with Latino farm workers in California, expressing the desperation of Appalachian miners left to wither without the dignity of work, Kennedy became a stunningly powerful voice for the excluded. Calling upon common qualities of indignation and conscience, he sought to touch "the enduring and generous impulses that are the soul of the nation."

In the California primary that he won the night he was shot, voter turnout was higher in Watts than in Beverly Hills. He was killed reaching out to shake the hand of a

$75-a-week dishwasher.

Kennedy's call was to justice and to democracy, not just to charity.

"Through no virtue of our own," he repeatedly claimed, we have been "born in the United States under the most comfortable conditions, (so) we have a responsibility to others who are less well off." Our "whole nation is degraded" by relentless poverty amid astonishing plenty. For Kennedy, "he who dismisses the outcast and the stranger...also denies America." A society of infinite possibility cannot accommodate itself to wrenching inequality and debilitation. To do so, "ignores our common humanity and our claims to civilization alike." Kennedy sought to tap "America's enormous reservoirs of hope" to make the promises of democracy real.

These sentiments must seem alien to our present generation of political leaders. Both parties forcefully turn their gaze away from those lodged at the bottom of American life. We govern for the powerful, we play to the privileged, we ignore those whom we need not see. We literally cut child tax credits for the working poor to provide dividend income shelters for the super-rich. And we are unembarrassed about it. Robert Kennedy would find today's politics unworthy, unwise, ungenerous and un-American.

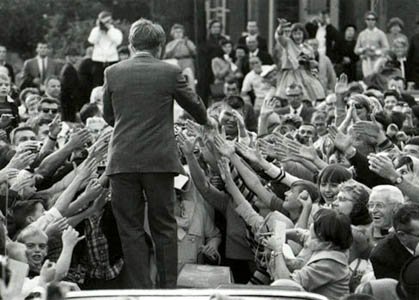

A few years ago, I read a moving tribute that Peggy Noonan had written about Kennedy. "To have known there was a politician who didn't like the greedy and the stupid," Noonan wrote, "but preferred the modest or even the strange." To have seen this "bright, believing man summon from us the faith that we could make America more decent if we joined together" changed a generation. This call, more than celebrity, is why millions reached feverishly for Kennedy's hand. His dramatic, ennobling sense of mission; his jolt of high purpose. For many of us, Kennedy's was the only politics of values, the only politics of heart, we'd ever known.

The world, as I said, is very different now. None challenge us. None shine a light on our darkest corners. None charge us to demand more of ourselves. None deal in hope. None barter dreams.

But when I see a silhouette of Kennedy straining to keep his balance on the back of a moving car -- shoulders sloping, eyes shining, hair disheveled, cufflinks torn from his wrists – part of me still reaches for his hand.

(Gene R. Nichol is dean and the Burton Craige professor of law at the UNC School of Law.)

Kennedy's call was to justice and to democracy, not just to charity.

"Through no virtue of our own," he repeatedly claimed, we have been "born in the United States under the most comfortable conditions, (so) we have a responsibility to others who are less well off." Our "whole nation is degraded" by relentless poverty amid astonishing plenty. For Kennedy, "he who dismisses the outcast and the stranger...also denies America." A society of infinite possibility cannot accommodate itself to wrenching inequality and debilitation. To do so, "ignores our common humanity and our claims to civilization alike." Kennedy sought to tap "America's enormous reservoirs of hope" to make the promises of democracy real.

These sentiments must seem alien to our present generation of political leaders. Both parties forcefully turn their gaze away from those lodged at the bottom of American life. We govern for the powerful, we play to the privileged, we ignore those whom we need not see. We literally cut child tax credits for the working poor to provide dividend income shelters for the super-rich. And we are unembarrassed about it. Robert Kennedy would find today's politics unworthy, unwise, ungenerous and un-American.

A few years ago, I read a moving tribute that Peggy Noonan had written about Kennedy. "To have known there was a politician who didn't like the greedy and the stupid," Noonan wrote, "but preferred the modest or even the strange." To have seen this "bright, believing man summon from us the faith that we could make America more decent if we joined together" changed a generation. This call, more than celebrity, is why millions reached feverishly for Kennedy's hand. His dramatic, ennobling sense of mission; his jolt of high purpose. For many of us, Kennedy's was the only politics of values, the only politics of heart, we'd ever known.

The world, as I said, is very different now. None challenge us. None shine a light on our darkest corners. None charge us to demand more of ourselves. None deal in hope. None barter dreams.

But when I see a silhouette of Kennedy straining to keep his balance on the back of a moving car -- shoulders sloping, eyes shining, hair disheveled, cufflinks torn from his wrists – part of me still reaches for his hand.

(Gene R. Nichol is dean and the Burton Craige professor of law at the UNC School of Law.)

Thank you for this. I lived through the time of the assassinations and, while JFK's shocked me out of my childhood, it was RFK's that hurt the most. I can't describe the despair and fear I felt at his passing, like the light had gone out for good.

ReplyDelete